The Lord Lonsdale Challenge Belt

A Belting Good Idea

By John Harding

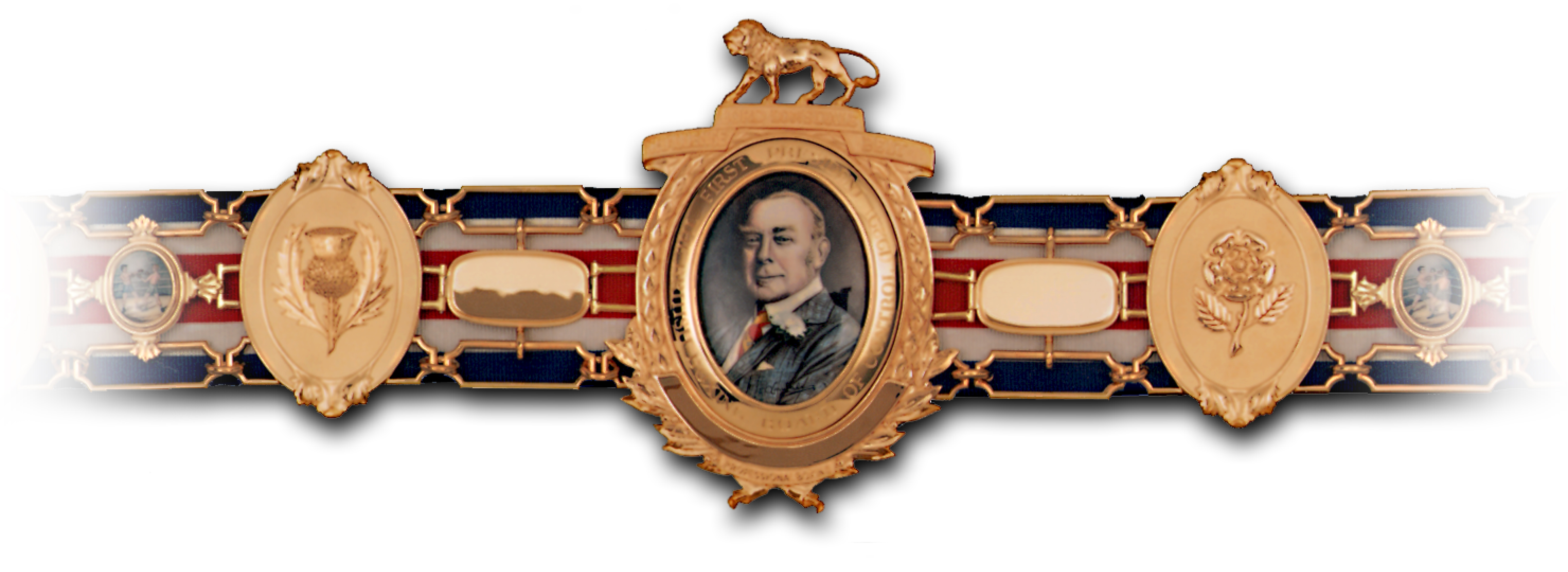

The Lord Lonsdale Challenge belt is undoubtedly the most beautiful of all sporting trophies, but its origin had nothing to do with aesthetics. Rather, it was a regulatory. Boxing as a commercial sport boomed in the early 20th century, but there was no governing body to ensure that fighters, promoters and the paying public adhered to either the law of the land (the police could intervene if a fighter died and arrest his opponent on a charge of manslaughter or even murder) or the Queensbury Rules (drawn up in the late 19th century but not always strictly applied.) What’s more, the proliferation of ‘champions’ at various weights threatened to devalue the sport’s appeal.

As bare-knuckle fighting faded in popularity, and as the Queensberry Rules introduced a semblance of continuity and shape to the fight game, ‘championship’ belts were awarded on a regular, even systematic basis and by the early 1900’s, rival venues such as Wonderland in London’s East End, the Cosmo in Plymouth and the National Sporting Club itself were competing to proclaim the ‘true’ champions.

It was because of the ensuing confusion that the National Sporting Club decided to institute its own ‘official’ belt series. In deciding on eight specific weight divisions with a trophy attached to each, the self-proclaimed ‘Home of Boxing’ was presenting the professional sport with a challenge: either concede to it the right to crown British champions and, in effect, grant it the authority akin to that wielded by the Football Association in soccer or the MCC in cricket; or continue to behave in random fashion, recognizing no central authority and thus run the risk of seeing boxing eventually outlawed - a prospect by no means impossible during the first decade of the century.

It was a gamble – but then, wasn’t that the principal raison d’etre of the NSC! Fortunately for boxing’s future, it paid off.

The original conditions attached to the winning of the new belts were simple: any boxer holding one had to defend it within six months after the receipt of a challenge for a minimum stake of £100 a side (£200 for heavies, £50 for flyweights). Before each defence, he had to deposit the belt with the manager of the Club; and he was also obliged to insure the trophy ‘against loss or damage by larceny and fire in the sum of £200’ - this amount to be deposited with the NSC as security.

The belt could be won outright, however, if the holder was declared the winner of three championship contests, consecutive or not, but held under the auspices of the NSC. If there were no challenges he could still become absolute owner if he remained undisputed holder for three consecutive years. Once undisputed owner, he was entitled to a pension of £1 a week for life on reaching the age of fifty. Most significant of all, however, the holder of the NSC belt (soon dubbed the Lonsdale Belt, after the Club’s president and donor of the first belt) could claim to be the undisputed champion of Britain – a designation not to be dismissed lightly, as it guaranteed the biggest purses and the biggest prizes.

Nevertheless, the first-ever bout, that between Freddie Welsh and Johnny Summers for the new lightweight limit of 9st 9lbs, almost didn’t happen. Both boxers already had lucrative contracts to fight elsewhere, not to mention proposed music-hall tours. There were arguments concerning cinematic film rights and side-bets amounting to thousands of pounds – added to which, Summers fell ill and requested a postponement with just three weeks to go! However, publicity for the match was unprecedented and Welsh’s ultimate victory – on points after twenty hard-fought rounds on the 8th November 1909– saw him borne from the ring in triumph while his seconds carried on a brisk ring-side trade in the sale of his bloodied and sweat-stained inter-round handkerchiefs!

Thereafter, Welsh occupied himself with money-matches rather than defending his prize. He had only two more NSC lightweight contests: he lost a return to Matt Wells, won the rematch, before heading off to the USA where he, and the belt, would remain. The NSC ultimately allowed him to keep it by default – and it was last seen being offered by a fight promoter to the winner of a World Lightweight bout in 1931.

However, the contest had launched the first Golden Era of British boxing, a period during which legends of the fight game such as Jimmy Wilde, Digger Stanley, Jim Driscoll, Johnny Basham, Dick Smith and Bombadier Billy Wells all claimed the ultimate prize – their very own golden belt.

The NSC would eventually decline in authority and power, and by the 1920’s, moves were made to establish a proper boxing board with clear authority. Once again, it would be Lord Lonsdale himself who would challenge those preferring anarchy to organisation and, on February 11th 1929, the British Boxing Board of Control was established. The new Board wasted no time in issuing a new Belt – this time with a portrait of Lord Lonsdale himself adorning the central panel. Originally of 9 carat gold, like the first series, the BBBoC belts would come to consist of silver gilt – hall-marked standard silver, gold-plated, but no less attractive and desirable. And once the great Henry Cooper had managed the remarkable feat of winning three belts, the Board decided that only one belt could be won outright by any boxer in any one division.

100 years on from that first contest in the smoke-filled Covent Garden headquarters of the NSC, the Lord Lonsdale Challenge Belt remains as tantalising and desirable a prize as any in organised sport. There may be bigger prizes on offer in terms of World and Continental titles, purse money and sponsorship, but to win a Lonsdale belt for keeps is the dream of all British fighters – not to have managed it, the regret of those who chose hard cash. Like an Olympic Gold medal, it’s lustre remains long after the cheers have died down.